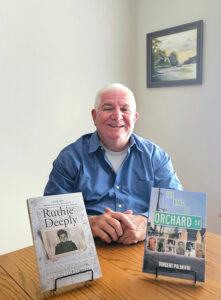

LAST PAGE: Vincent Palmieri, 70

Author’s books convey the colorful people and places he came to know while growing up in Frankfort, a small town in Herkimer County

By Mike Costanza

Q. “Ruthie Deeply,” your first book, is a deep dive into the rough life of family friend Ruth Morgan. Could you tell us about her?

A. I chose Ruthie Deeply because she and I pursued her full story deeply. Ruthie is a woman that I have known all of my life. She was abandoned in 1934, ends up in the state school in Geddes [a town outside Syracuse]. It’s state-sponsored torture. She was probably the worst-behaved person in the place, because that’s all she knew, how to fight. Finally, at 24 years old she’s released. She didn’t know how to read and write. She didn’t know how to buy a pair of shoes. She ends up across the street from me. The story chronicles her, from when we could piece together as best we could, 8-9 years-old, until the book was published. She married, marriage went bad, she had three children. She’s 91 years old now, she’s healthy and happy. She lives in Ilion. She’s a warrior. She did well for herself.

Q. What do you want readers to learn from Ruth’s story?

A. Resilience. Never give up. It makes no difference where you start. The difference is where you end. She did all right for herself and continues to do all right for herself.

Q. “The King of Orchard Street” presents your memories of growing up on Orchard Street and the reminiscences of five relatives or friends who once lived there. Can you tell us about the book?

A. Frankfort is a very small community, only about 2,200 people. Everybody knows everybody. We all tell our stories, which many of them intersect. Then the reader decides, in a whimsical way if nothing else, who is the king of Orchard Street. Which one of us was the baddest hombre on the street, as a fun kind of thing.

Q. How did you become the “baddest hombre” on Orchard Street?

A. Behind my grandmother’s house was railroad tracks. My mom and dad would say “Don’t you go near those railroad tracks.” I tripped on a rock, hit my head on the railroad track; went in the house showing a little blood. I’m screaming and crying. She [his mother] gets it to stop. An hour later, my father walks in. To make me feel better, he takes a towel and he wraps it around my head and he puts a feather in the back of it like an Indian. Right there, I’m transformed not to the king of Orchard Street; I’m transformed to the king of the universe. After 63, 64 years I’m still giggling about that story.

Q. What do you want people to take from “The King of Orchard Street”?

A. The lifestyle it paints. It was a different world then, with kindness, acceptance. Once you were there, you were accepted. You were on the team. Everybody was treated equally. If you got ahead, you almost had an obligation to help other people get ahead.

Q. Have you continued to write?

A. Now that my first two books are published, I’m on a new book. It’s actually a story that I started in 1977. The name of it at that time was “Tarnished Gold.” I changed it to “Medals.” This is an Olympic story.